| — WARNING — |

| This article belongs to the monster history category of pages, which detail the creatures of the Monster High franchise and do so in relation to the source context of those creatures. There is a likelihood that this article contains material not suited for young people and in general holds topics that are upsetting. If you only wish to read about the basic inspiration choices for the Monster High characters and creatures, go to |

The Grim Reaper is the most common personification of death in European and European-descent contexts. The general depiction is of a skeleton figure, who may either walk or float, largely shrouded in a black and hooded cloak, and carrying a scythe and hourglass. As death, the Grim Reaper's job can be divided in three tasks, though it depends on the story which tasks are attributed to them. The three tasks are to announce death, to execute the person marked for death, and to guide or take the deceased to the realm of the dead. Though the Grim Reaper in folklore is considered a singular or rare entity, in literature and other consciously written media multiple reapers are not uncommon. In Monster High, too, there are multiple grim reapers. In Monster High, like River Styxx, some grim reapers or Grim Reapers are a combination of skeletons and ghosts, not in the hybrid lining. In Monster High, they also appear to be a borderline of ghosts and skeletons.

Etymology

The term "Grim Reaper" first shows up in 1847 according to the Oxford English Dictionary, though its simpler alternative "Reaper" is at least as old as the 1650s. Before settling on "Grim Reaper", the alternatives "Old Reaper" and "Great Reaper" also floated around.

The word "grim" exists as both an adjective and a noun, though the latter is rarely used these days. "Grim" as a noun is either synonymous to "spirit" or a type of spirit. This meaning goes back to the 1620s. "Grim", as both an adjective and a noun, can be constructed back to a Proto-Indo-European word "ghrem", presumed to mean "angry" and an onomatopoeia for a rumbling or growling sound. "Grim" used to be a stronger word than it is now and was associated with death at least by the 17th century. Similarly, the verb "to reap" from which "reaper" comes shares its sound with words in many European languages all coming down to mean "taking (regardless of the wishes of anyone else)".

History

Development

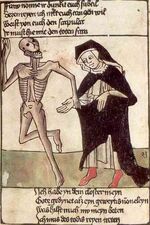

In Europe, the personification of death went from passive and on-specific symbolism to an aggressive pseudo-defined entity in response to the disasters of the 14th century, in particular the devastation brought by the Black Death. To deal with this trauma, several genres and motifs relating to death developed, such as the Memento Mori, the Ars Moriendi, and the Dance of Death. The first is a theme about the need to remember that death is at the end of every life and that what is done in life has to matter, or at least insofar that it nets one a nice spot in the afterlife. The second is advice on how to die a proper Christian death, again in regards to a nice spot in the afterlife. The Dance of Death is an artistic fusion of the way the Black Death kills anyone regardless of social status — thereby upsetting century-old power systems — and the desire to enjoy life until the final moment that could come at any time. In the first few centuries, the Dance of Death was usually expressed as an image or a play so everyone from the largely illiterate population could understand it. A Dance of Death typically includes at least one corpse and one living person. They do not have to be literally engaged in dancing, but this or a lead-up to this was common. Elaborate art pieces contained multiple living persons in the presence of one or more corpses, with the living persons explicitly representing various social classes. Because women weren't allowed access to many classes, the living persons in Dance of Death pieces tend to be men, although the pairing of a corpse and a young woman, a being not only full of life herself but also capable of creating more life, provided enough story to develop into its own motif: Death and the Maiden.

The imagery involving a singular corpse developed into identifying said corpse as Death itself. Death was initially unclothed, but by the end of the 15th century the entity started being depicted in a burial shroud or the remnants of one, which further down the line developed into the black hooded cloak, sometimes specifically a cowl, iconic to the Grim Reaper these days, although locally, such as in Poland, the cloak can be white too. Occasionally, Death was depicted with feathered wings to represent its ability to reach any place, a presentation that continues to this day but is not considered essential to the appearance of the Grim Reaper. Rising from the Dance of Death motif, Death occasionally shows up with a musical instrument to lead the dance in the first few centuries of their existence, though weaponry has since early on been a more common attribute of the Grim Reaper. The popular ones in the first few centuries are arrows and the scythe. Death is rarely depicted carrying them both. Arrows, with or without a bow, have a long history as symbolizing death that cannot be defended against or comes unexpected — this was during the time disease was thought to be caused by bad air — and they carry a distinct message of divine authority that extends well beyond European borders. During the Late Middle Ages, they are particularly but not exclusively related to death by disease, the Black Death. The scythe functions on two levels. On one hand, in reality scythes are a terrible choice of weapon, so depictions of it as weapon are rare. Imagery of a supernatural entity wielding one are unexpected and therefore marked with an extra layer of terror. On the other hand, the scythe makes the deceased the harvest and with harvest being an essential and natural part of life, death is made more acceptable. The time of the debut of the hourglass, second only to the scythe in current day depictions of the Grim Reaper and representing the inevitability of death, is unclear, but it was a commonly used symbol in the early years of the 16th century. Both the scythe and the hourglass are also attributes of Father Time, suggesting a common source with the Grim Reaper. If so, this would be Chronos and Kronos as they appeared in Greek mythology. Chronos is the god of time and Kronos of harvest, among others. Due to the similarity of their names, they've been conflated even during the time of their religious relevance. Kronos was a cruel god, best known for eating his own children and castrating his father with a sickle, which is essentially a small scythe. Coupled with Chronos's theme of time, the resulting entity embodied the temporary nature of life and inevitability of death, but also eternity and the succession of generations.

Attributes of the Grim Reaper barely used anymore are an extinguised or almost burned up candle and a bell. Both are about as old as the hourglass, but are rarely used in new works featuring the Grim Reaper. Rarely, Death used to be depicted to wearing a blindfold for the same reason as Lady Justice still does: to communicate absence of prejudice. An attribute of recent nature is the ace of spades, which is considered the death card. The history behind this is not clear and suggestions vary from the association of the spade with the digging of a grave to the cards representing weeks of the year and the ace of spades being associated with the start of winter. Though the ace of spades as the death card goes back a while, common understanding has its origins in the Vietnam War of 1955-1975. The American soldiers made the assumption that the people of Vietnam were highly superstitutious and understood the ace of spades to stand for death due to exposure to French culture during colonial times. From there a plan formed to leave ace of spades cards on the bodies of their victims and investigated villages as a form of psychological warfare. In truth, the assumption was thoroughly incorrect and the use of the cards was more a way for American soldiers to feel like they'd accomplished something than a way to add insult to injury. The practice also wasn't nearly as common as the whole of stories portrays it to be. Ace of spades cards made their way into movies about the Vietnam War and that made the card's symbolism known among a larger audience. Association with the Grim Reaper happened soon after.

Views of the Grim Reaper have changed over time, becoming more positive in times when survival was not a constant concern. The Grim Reaper is also treated as a more passive and even sympathetic entity who only guides souls during these good times instead of an aggressive one who performs the actual killings. At times, Death is portrayed as an entity functioning between God and the Devil. Death is the one who collects the souls unbothered while the other two eternally fight over who will obtain them. Alternatively, the image of the Grim Reaper, already occasionally sat on a horse, proved so popular that by the 19th century Death from the biblical Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse came to be depicted in the same way. Of the four, Death is the only one identified and the only one who explicitly carries no instrument but instead drags along the underworld. The Grim Reaper reimagining tends to replace the underworld with the iconic scythe. As horseman, Death's horse is said to be "khlōros", an Ancient Greek word that can mean both "white" and "green". Depending on the work, it is interpreted to mean "(sickly) pale", "ghostly", or "(decomposition) green". (It is explicitly not just "white" because the horse of the first horseman already is unambiguously white.)

Though by nature a genderless entity, the Grim Reaper is commonly interpreted as male or male-leaning. Most European languages that assign gender to nouns utilize a female "death", though, and in early times personifications of death were, if gendered, usually female. Influence from North America, which had inherited the male Grim Reaper, pushed the adaption of the male entity across Europe. One result of this is that the Grim Reaper in a few languages is grammatically female, such as the French La (Grande) Faucheuse and the Spanish La Parca, which originally were terms in use for female variations. That said, the aforementioned Death and the Maiden motif that developed late in the 15th century also contributed to the spread of the male personification as it required Death to contrast with the Maiden. Death and the Maiden takes inspiration from younger versions of the Persephone and Hades story in Greek mythology. In short, Hades, god of the underworld, falls in love with Persephone, daughter of the goddess of harvest and a harvest goddess in her own right, and therefore abducts her to the underworld. Distraught, Demeter refuses to perform the duties left to her, with famine as a result. The other gods agree to get Persephone back, but she has already become bound to the underworld. An arrangement is agreed upon that Persephone will live half the year with her mother, this time becoming Spring and Summer, and half the year with her husband, this time becoming Fall and Winter. This story itself is an adaption of older myths, both Greek and other, that have been altered from a context of female equality as Ancient Greek society grew more misogynist. Similarly, the Death and the Maiden motif, as maintained by male artists, is a predominantly misogynist one. Though a portion of the work is dedicated to the opposite qualities of the two participants, many more examples of it feature Death as sexually aggressive and overpowering.

Other Deaths

The Grim Reaper is part of a complex network of death-related entities whose traits have influenced each other over time. Greek mythology, which was hugely influenced by Egyptian mythology and the Mesopotamian mythologies, held many death deities, most of whom were the children of Nyx, the goddess of the night of the primordial branch of the the Ancient Greek gods, and siblings to the sleep deities and fate deities. The most well-known of these deities is Charon, who helps the deceased across one of the five rivers in the underworld. In Greek and Medieval texts, this is the Acheron, while it is the Styx in several Roman works, notably Vergil's Aeneid, which was written between 29 and 19 BC. As ferryman, Charon qualifies as a psychopomp, albeit an unusual one because he requires payment before he does his job. He is commonly depicted with his rowing pole and starting the 20th century he is dressed in a cloak inspired by the Grim Reaper. Between dying and meeting Charon, the deceased were gathered and guided by Thanatos, god of (gentle) death and twin brother of Hypnos, god of sleep. They too were children of Nyx, and were winged beings whose symbols included poppies and upside-down burning torches. Of the other death deities, of note are the Moirai, who double as fate deities. They are Clotho, who spins the threads of life, Lachesis, who measures the length of each thread with her rod and assigns its fate, and Atropos, who cuts the threads with her shears. In Plato's The Republic of around 380 BC, they are assigned insight into the past, present, and future. As a goddess trio, their mythology starts as one goddess that underwent triplication. Atropos, also known as Aisa and Moira, is the original, being a goddess of death and becoming a goddess of fate as part of the trinity. In Roman mythology, the Moirai are known as the Parcae. The Spanish La Parca is named after them and specifically refers to Morta/Atropos.

Though the part about payment appears to start with the Greek Charon, the concept of the psychopomp as a ferryman is older. An analogous entity appears in Mesopotamian mythologies under a number of names, the oldest one still fully known today being Urshanabi. He helped the deceased over the Hubur and can be found in texts dating from the second half of the third millenium BCE. Today, he is best known for his appearance in the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem from around 2100 BCE. The protagonist, Gilgamesh, meets him after the death of his friend Enkidu and Urshanabi becomes something of a second companion to him. There is thematic overlap between parts of the Epic of Gilgamesh and parts of Homer's Odyssey from shortly before 700 BCE, of which Gilgamesh's journey to the realm of the dead and encounter with Urshanabi and Odysseus's journey to the realm of the dead and encounter with Charon is one. A seemingly even older ferryman of the dead is the Ancient Egyptian Cherti, who can be found in texts dating from the first half of the third millenium BCE. Among others, he is mentioned in the Pyramid Texts of 2400-2300 BCE. He has the head of a ram and rules the commoners' level of the underworld on behalf of Osiris. Towards the end of the third millenium BCE, Cherti develops into two new ferryman, Aken and Mahaf, who take his place in the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead. Aken essentially is Cherti, but he sleeps between customers and can only be awakened by Mahaf.

Closely related to the Grim Reaper is the Angel of Death. Unlike the Grim Reaper, the Angel of Death is not a defined being, but a concept that wavers between a title and an entity. Sometimes, the Grim Reaper and Angel of Death are one, especially when the Grim Reaper is depicted with wings. Other times, the Angel of Death is an alternative to the Grim Reaper. A common depiction since the 1850s is of a woman, either with human skin color or deep white skin, dressed in black and in the possession of black feathered wings. The Angel of Death has their origins in the Abrahamic religions and like all angels is either male or male-leaning. All angels have one or more tasks assigned to them and one or more are the designated executioner or psychopomp, although none of them perform outside of the Supreme Being's explicit orders. The identity of these angels depends on the religion: Azrael is the one from (parts of) Islam, Michael sometimes hold the title in Christianity, and Judaism has Sariel and Samael. Several other religions have their own Angel of Death or share with one of these three, and the aforementioned three have some internal variation depending on the source. The currently common idea of angels looking like winged humans does not exist within the source material but comes from design developments in the fourth century CE and likely have been inspired by depictions of various winged deities of religions prior. Angels as female or female-leaning is a development from around 1800 in European contexts. At this time, religious control was in the process of losing ground and angels were separated from religious context and became available for reinterpretation as artists and donors pleased. Through this, the Angel of Death has become a fluid concept.

Unambiguous alternatives to the Grim Reaper as Death also exist in Europe, though they are either local or limitedly used. An example of a unique depiction of Death from the Grim Reaper's origin age occurs on a fresco inside the Saint Andrew Abbey of Lavaudieu in France. It dates from 1355 and represents Death as a fully clothed and distinctly uncorpselike woman with covered eyes. She carries arrows with her and is surrounded by people she's punctured with them. This Death is tied to the Black Death, her arrows having landed in places where the swellings tend to manifest.

The Ankou is a personification of Death closely related to the Grim Reaper but with a vast history of its own. It principally belongs to the folklore of Brittany but is also present in those of Cornwall and Normandy. The ankou is an entity that in some cases is singular, then being a cursed prince who lost a hunting match to Death, or more commonly is the last person to die in a particular year within a parish, meaning there's as many ankou as there are parishes and succession happens on a yearly basis. Alternatively, the ankou is the first to die in a particular year or the first person to have ever died and been buried within a parish. The ankou is not Death itself necessarily, but its henchman, and though anyone can become an ankou, the ankou is never depicted as anything but an adult man. The task of the ankou is to protect their parish's graveyard and to collect the souls of the deceased to bring them to the afterlife. For this purpose, they ride a coach, but they can also bring a wheelbarrow or operate a nightboat. In case of the more common coach, the ankou tends to have two spectral helpers and the coach is pulled by either two horses, four horses, or goats. In all cases, the animals are supernatural themselves, and the horses have manes reaching to the ground. The ankou can look identical to a grim reaper, but more characteristically they wear a black cloak, a wide-brimmed hat, and a scythe with a reversed blade. The ankou can be skeletal, but also any other form of corpse, and the owl is associated with the entity. Depending on the legend, by day the ankou resides within their graveyard or at Monts d'Arrée. Hearing the wheels of an ankou's vehicle is a message of death, either the hearer's or someone known to the hearer. Though the exact history behind it is unclear, the ankou is recognizable as a fusion of the Grande Faucheuse/Grim Reaper and various creatures from folklore mostly specific to the British Isles, such as the dullahan and its death coach, the banshee, and the church grim.

A productive artist of imagery involving the Grim Reaper was Alfred Rethel. He depicted the entity in many different ways, ranging from dangerous to sympathetic if not tragic and from a higher being to "one of the people". One image stands out for its use of a secondary manifestation of Death. In 1832, the second cholera pandemic hit Paris. It was a time not unlike 500 years before with the Black Death and celebrations were held to escape the cruel reality. The poet Heinrich Heine found himself in the middle of it, but survived and wrote down some of his experiences. One imagination-provoking passage reads — translated — as follows: "That night, the balls were more crowded than ever; hilarious laughter all but drowned the louder music; one grew hot in the chahut, a fairly unequivocal dance, and gulped all kinds of ices and other cold drinks--when suddenly the merriest of the harlequins felt a chill in his legs, took off his mask, and to the amazement of all revealed a violet-blue face. It was soon discovered that this was no joke; the laughter died, and several wagon loads were driven directly from the ball to the Hotel-Dieu, the main hospital, where they arrived in their gaudy fancy dress and promptly died, too...[T]hose dead were said to have been buried so fast that not even their checkered fool's clothes were taken off them; and merrily as they lived they now lie in their graves." Rethel used this passage in 1851 as inspiration for the aforementioned image, which shows the Grim Reaper playing music on an instrument made of bone while a female figure representing cholera sits quietly in the back.

In Scandinavia, where the Black Death hit last, a different personification was created, namely Pesta also known as the Plague Hag. Pesta is an old woman dressed in a black cloak who visits towns with either a rake or a broom. If she brought the rake, some of the town would go through the teeth and survive. If she brought the broom, everyone would be swept away and perish. During the Black Death, many towns were entirely wiped out, only to be found later by travelers either passing by or coming to look for family they hadn't heard from in a while. The most famous depiction of Pesta comes from Theodor Kittelsen, who claimed to have encountered her.

The Southeastern area of the German-speaking countries of Europe, probably influenced by the female Death of neighboring countries, has folklore featuring both a male Death and a female Death, who often are a couple. The female Death is called Die Tödin or Die Tötin, a feminization of the masculine "der tod" that only occurs to refer to the entity. As a couple, der Tod and die Tödin work together — he executes those marked for death with his scythe and she gathers the deceased with her rake. Die Tödin also concerns herself with washing funeral clothes and it is considered unsafe to let one's own laundry outside for the night. This will confuse die Tödin, who will wash the laundry along and then hang it back. Those who wear what she washed will die. How der Tod and die Tödin visually appear depends on the story, and die Tödin can alter her size in some stories, which she uses to scare people.

Outside of Europe, a special development occurred in Latin America. During colonial times, the Europeans active in that area did much to destroy local religions and implement Christianity until the Latin American wars of independence during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In New Mexico and southern Colorado, the departure of the Spanish left the population with their half-forgotten original religion and half-understood enforced religion and in this vacuum, they created something new. Placed at the center of the newly formed Penitente Brotherhood was Doña Sebastiana, a female Death travelling in her Death Cart and in the possession of a bow and arrows. Her attire not set, nor is she guaranteed to wear clothes, and while she may have long brown or white hair, she may also be bald. Doña Sebastiana is theorized to be an amalgation of two figures against a background of death-positive old religions: La Parca and Saint Sebastian. Saint Sebastian was a martyr sentenced to be tied to a pole and shot with as many arrows as possible to kill him. Thanks to intervention, he survived and went back, this time to be clubbed to death, which he did not survive. His first death-to-be has proven more iconic for the saint and is how he's usually depicted. Due to the association with arrows, he became a protector against the plague, thereby already tying him to la Parca before the fusion into Doña Sebastiana. Doña Sebastiana would inspire or become Santa Muerte, a current-day folk saint paid respect to mainly in Mexico and the Southwestern United States. Her symbols are a scythe and a globe. Other folk saints similar to her, but male, are San La Muerte and San Pascualito.

In the company of humanoid personifications of Death or death-related concept, sometimes there are animal ones other than horses. The crow and raven are popular examples of birds, which is based on the European interpretation of the carrion-eating creature as a mediator animal between life and death. Vultures have been placed in the same range on USAmerican influence. Dogs, often easily recognizable as supernatural, show up as guards of the underworld in various mythologies. Butterflies and moths can be traced back to Ancient Greece to symbolize the soul. Cats, owls, and bats, as well as some of the aforementioned animals, are associated with death because of their association with the supernatural and the night, which in turn are associated with death.

Fiction

Though not by origin a story about the Grim Reaper, the Christian prophecy of the end of the world as detailed in the Book of Revelation features a personification of Death commonly conflated with the Grim Reaper. The prophecy claims that God possesses a scroll that is seven times sealed. The Lamb of God will open them when it is time for the apocalypse and the first four will summon four horsemen in order. The text is not clear on who these horsemen are, as only Death is mentioned by name. Generally, the second and third are agreed upon to be War and Famine, and it's mostly the first horseman that causes disagreement. That is, the common interpretation is that they are Conquest, but whether it is the conquest of the Christ or the Antichrist. Regardless, in this interpretation the horsemen represent a series of events that will be the first half of the apocalypse. For reasons that are uncertain, an alternative interpretation of the first horseman is Pestilence. This interpretation is found earliest in the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906 and so is fairly certainly a 19th century development, succeeding Death as the Grim Reaper by a century or so. Theories to this interpretation are the fact that the first horseman carries a bow, arrows having both symbolism to the divine and disease, and the line "They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine, plague, and by the wild beasts of the earth," found in the fourth horseman's part. It is, however, unclear if the line refers to all the horsemen or only the fourth and the "wild beasts" part is ignored altogether. With the first horseman as Pestilence, the horsemen become more easily readable as manifestations of suffering, if need be detached from the religious origins. This is why current-day fiction featuring them usually identifies them as Pestilence, War, Famine, and Death.

In European context, there exist a handful of fairytales and fables featuring Death. There are about three distinct common ones and the rest is a variation on the same themes. The first is The Old Man and Death, one of Aesop's Fables from the 6th century BCE. It is one of the fables translated and adapted by Jean de La Fontaine in the 17th century; twice no less. The basic story is about an old woodman carrying a large bundle of sticks on his back. Exhausted, he casts it down and calls for Death to end his misery. To his surprise, Death does come and asks him what he wants. The woodman quickly asks him to carry the sticks for him, not risking to admit he said he'd rather be dead. Secondly, Godfather Death is the name under which the Brothers Grimm collected one of the fairytale variations. The first part of the fairytale concerns a father looking for a godfather for his son and picking Death after rejecting God and the Devil because they are dishonest. Death later makes his godson a physician by allowing him to see if a patient will live or not. If Death stands at the patient's head, that person is to be given a special herb found in the forest to live, but if Death appears at the patient's feet, they will die no matter what. All is well until the king falls deathly ill and the godson turns the bed around to cheat Death out of his loot. Despite warnings from Death not to do that again, when the princess falls deathly ill and the godson is promised her hand and the kingdom if he saves her, the godson tricks Death again. For this, Death takes his life. Primary variations deal with the motives of the godson, whether he tricks death for own gain or out of pity for his patients. In the latter case, he tends to be given the choice to replenish his own life by taking another's, but chooses his own death over anyone else's. Alternatively, focus is placed on the three encounters early in the story that play little role in Godfather Death. One variant has a soldier or merchant come home to his town after a long absence. He has a meal in the open a few days before arrival and is approached twice by saints who ask for a share, but he chases them off both, accusing them of dishonesty. When Death shows up and asks for a share, the man invites him eagerly, arguing that Death is always unbiased. Death accompanies him to his town, where they arrive to find it in mourning. The man asks why everyone is crying and Death explains it's for him. For insulting the saints, they sent Death to end the man, but the man's kindness made Death choose to leave him long enough that he could reach home. Death, too, is not always unbiased. As third variation of the fable and fairytale whole, there are many stories in which the Devil is tricked and often there's a variant in which the Devil is replaced with Death. Whereas the stories in which the Devil is tricked tend to have happy endings, stories in which Death is rarely do. The protagonist finds the world suffering without death, prompting them to release Death and either die themself on the spot or find Death to leave them alone permanently to let them suffer disease and old age for eternity.

Lenore was written in 1773 by Gottfried August Bürger and published a year later, with an English translation following in 1796. It was well-received and became one of the core works in the gothic horror genre as the main influence on the narrative of the dead returning to reunite with a beloved still alive. The poem concerns one Lenore, whose fiancé, Wilhelm, does not return from Battle of Prague. She curses God, proclaiming that she does not care anymore about either her soul or her life. That night, Wilhelm returns and asks for Lenore to join him to their marriage bed. Overjoyed, Lenore climbs on Wilhelm's black horse and the two leave. Lenore does not become concerned until Wilhelm sets a dangerously fast pace. At sunrise, they arrive at a cemetery. As he starts to change shape, "Wilhelm" reveals the marriage bed to be the grave where Wilhelm's corpse lies. Showing himself as Death, complete with scythe and hourglass, Lenore has little time to dwell on the deception as the ground beneath her begins to crumble. Punished for her rudeness, Lenore accepts death, but hopes her soul will be spared.

In 1798, Samuel Taylor Coleridge published his poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Though receiving mixed responses in its time, the poem found itself popular enough with other writers to be referenced and eventually reach the fame it does nowadays. It has been made into a movie twice. The poem tells of a sailor, the titular Ancient Mariner, who on one voyage ended up stuck in the ice of Antartica. An albatross comes to the ship and guides it out of the cold waters, but the sailor shoots the bird anyway. This turns the spirits of the area against the ship and its crew and the sailor's colleagues force him to wear the dead albatross around his neck. As they drift into uncharted waters, they encounter a ghost ship. Aboard are two beings: Death and a woman described as having red lips, few or loose clothes, golden locks, and skin as white as leprosy. She is identified as "The Nightmare Life-in-Death" and theorized to form a couple with Death. The two are casting dice, which wins Life-in-Death the sailor and Death the rest of the crew. All of the sailor's colleagues fall dead soon after, leaving the now-immortal sailor to suffer alone. Eventually, he makes it back to land, where he finds himself afflicted with a compulsive need to tell his story to others as he goes to roam the earth. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is one of the few depictions of Death as part of a group, although its origin seems to lie in the well-known Death and the Maiden motif, and a rare story that features what arguably is an anti-Grim Reaper, as Life-in-Death forces eternal life and with that eternal suffering on her targets.

The Masque of the Red Death is an oft-referenced short story by Edgar Allan Poe published in 1842. Its protagonist is Prince Prospero, who has gathered all the nobles of his land and locked himself with them up in his castle so they'll avoid the Red Death that is wrecking havoc among the commoners. To pass the time, the prince organizes a masquerade ball in seven of the rooms of his castle, all color-coded. Though entertaining, no one is willing to enter the seventh room, which is black, illuminated by red light, and home to an ebony clock which hourly strikes can be heard through the rest of the rooms. At midnight, a stranger appears among the crowd, dressed in a blood-splattered funeral shroud and a mask resembling the countenance of a corpse. The stranger makes its way to the seventh room, to which only Prospero is willing to follow out of sheer fury. But once the two face each other in the seventh room, Prospero screams and falls dead, providing the guests with enough incentive to attack the stranger themselves. Taking off his robe and mask, they find nothing underneath, and fall down as victims of the Red Death, which in the end finds everyone. The antagonist of The Masque of the Red Death, while not a Grim Reaper proper, fits the history of the Grim Reaper and is often interpreted as him. The ebony clock mentioned in the story is matched with the entity and in essence is their hourglass. The disease the entity stands for, the Red Death, when not treated as a mere fictional construction, has been suggested to be tuberculosis, of which many of Poe's loved ones died, providing him with a lifelong obsession, the Black Death, given that the chase ends in the black room and the name similarity, and cholera. Only a decade before the publication of The Masque of the Red Death did the second cholera pandemic hit the West. There are similarities between the masquerade in face of a deadly disease as written about by Poe and as happened in Paris, which the general USAmerican public knew about due to the publications of the "Pencillings by the Way" by Nathaniel Parker Willis in the newspapers.

Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol was finished and presented to the public in 1843. It would become considered the quintessential Christmas, not in the least because it played a major role in redefining Christmas in the West and reviving interest in the holiday. It is one of the most retold stories of recent times. In short, the protagonist Ebenezer Scrooge, a miser who shuns social contacts outside business, is visited on Christmas Eve by the ghost of his business partner and last friend, Jacob Marley, who died seven years prior. He warns Scrooge that he is on the path of damnation and that tonight is his last chance for salvation lest he be forced to roam the earth in heavy chains as is Marley's fate in death. Three other ghosts visit him subsequentially: the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come, and in turn they show Scrooge's change into the man he is now, how the world outside his home is currently doing, and what the future will hold if to the current path is kept, which isn't pretty. On Christmas morning, Scrooge chooses to change, benefitting the fate of many in London. Each of the three Ghosts of Christmas presents differently. Past is angelic, candle-like, androgynous, and ever changing its shape, although most visual adaptions simplify it to the form of a young girl. Present is a rapidly aging tall man of pleasant appearance who shields Ignorance and Want under his robe. Adaptions generally stay faithful to the novel but for the removal of Ignorance and Want. Yet to Come is shrouded in a dark cloak, which conceals all of its form but for one hand. Yet to Come is associated with death and likely not coincidentally evokes the Grim Reaper in its appearance. Adaptions tend to emphasize the Grim Reaper context, some even making them explicitly the same. It is possible Dickens was inspired to the Ghosts of Christmas by the Moirai of Greek mythology, who too have the aspect of past, present, and future in some interpretations. At least, Dickens was aware of the Moirai by 1859, when A Tale of Two Cities came out. Its character Madame Defarge is part reference to them.

Thematically similar to A Christmas Carol is the 1912 novel Thy Soul Shall Bear Witness! by Selma Lagerlöf. Its tale concerns David Holm, who has tuberculosis, alcohol addiction, and a long list of pain caused to the people close to him. On New Year's Eve, he recalls the myth of the Phantom Carriage, namely that who dies last in a year has to assist Death by collecting the sould of the deceased for one whole year. Shortly after, he dies during a drunken fight and finds his friend Georges to be the driver of the Phantom Carriage and expecting him to take over for next year. David refuses, prompting Georges to force him along to the first to die that year, whom are all people David caused harm. He provides them peace in their last moments, but when he finds his wife and children ready to commit suicide after all the abuse he put them through, he begs for a chance to intervene. Georges grants him this, restoring him to life and taking the task of driver for another year. The novel proved popular enough to warrant three film adaptions: two in Sweden and one in France. The first of these, the 1921 movie The Phantom Carriage with Tore Svennberg in the role of Georges, is considered one of the central works in the history of Swedish cinema.

1944 saw the finalization of the script for The Lady of the Dawn, a play by Alejandro Casona. The Death of the story is female and goes by the title of The Pilgrimess. She is human in appearance and behavior, acting on hunch rather than knowledge and pitying herself for her own paradoxical immortality. She becomes involved with the Narces family when they have lost their daughter Angelica four years before and never found her body, when her husband Martin is supposed to die but doesn't because the Pilgrimess overslept, and when Martin brings home Adela whom he saved from suicide even though the Pilgrimess has no knowledge of her supposed death. Nonetheless, she feels Adela will succeed in seven months and promises she'll be back then to the grandfather, who recognized her from a near-death experience. Within the seven months, Adela grows into the role of Angelica, returning joy to the family after Angelica's unresolved death. Martin is the only one who knows Angelica is not dead, but ran off with a lover, but keeps it to himself out of respect. After seven months, the Pilgrimess returns to cut off Angelica, who is trying to return home after her lover abandoned her. The Pilgrimess realizes it is Angelica for whom she has come, as she has been replaced with Adela and can only ruin her family again. Angelica accepts this and as her body is found in perfect state despite being supposedly dead for four years, the town regards her as a saint. As Martin is now free to marry Adela, the Pilgrimess laments the monotony of her own existence once more.

The Seventh Seal is a 1957 movie written and directed by Ingmar Bergman that brings together various pieces of European material regarding Death and presents Death in Grim Reaper form, played by Bengt Ekerot. The movie was partially inspired by a 1480s fresco in Täby Church by Albertus Pictor. In Sweden during an anachronistically reconstructed version of the Middle Ages, Antonius Block and Jöns return from the Crusades to find their country stricken by the plague. During the journey by boat, Antonius had been playing chess by himself and when he finds himself and Jöns greeted by Death on the beach, he challenges him to a game, hoping to get a few things done before dying. Death accepts and as only few can see him, people simply assume Block continues his game against himself. Along the way to Antonius's castle, they meet and invite several people along, among which a family of actors. Sensing doom, the family tries to escape before arriving at the castle, which they succeed in due to Antonius distracting Death, although Death wins the game after tricking Antonius into revealing his strategy. At the largely deserted castle, Antonius reunites with his wife and the group enjoys a final meal before the plague claims them and Death fetches them in a Dance of the Dead. The Seventh Seal is a highly iconic movie and has been referenced and spoofed many times, among others by The Muppets and Monty Python. A notable parody sequence occurs in the 1991 movie Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey, wherein the titular characters return to life by defeating Death at Battleship, Clue, electric football, and Twister.

Frau Holle, better known in English as Mother Hulda, is a figure theorized to be the one of the current identities of one or more pre-Christian goddesses and though she became a folkloric entity she kept her aspects, much of which resonates within the fairytale. One such aspect is Frau Holle as a life-and-death entity, which Juraj Jakubisko used as a core aspect of The Feather Fairy in 1985. The character of Frau Holle is split into Frau Holle (Giulietta Masina), who represents life, and Frau Hippe (Valérie Kaplanová and Eva Horká), who is Death complete with scythe and the ability to appear old and young as she chooses. The two are close but disagreeing friends. Frau Holle takes a boy named Jacob in her care after Frau Hippe fails to kill him along with the rest of his community. By watching her through Frau Holle's crystal ball, he falls in love with Elisabeth and leaves the immortality Frau Holle has given him behind to be with her. This pleases Frau Hippe, who tries multiple times to kill him still and who finds unwitting aid with Elisabeth's stepmother and stepsister. Jacob outsmarts her every time but for one, which nearly kills Elisabeth. Frau Holle saves Elisabeth from Frau Hippe and intends to keep Elisabeth as her new companion, but when Frau Hippe lies about Elisabeth's death to Jacob to finally get him on his knees, Frau Holle sends Elisabeth back just in time. Frau Hippe accepts the lives of Elisabeth's stepfamily instead and agrees to leave the Jacob and Elisabeth alone until old age.

Influential to Death as the Grim Reaper in popular culture are the Discworld novels by Terry Pratchett, of which the first entry was published in 1983. Death itself, presented as a standard Grim Reaper, properly dates from 1987. As the series is comedy-fantasy, Death adheres to a large number of his depictions that are both poked fun at and are given a Discworld-specific context for them. Death in the novels is specifically the Death of the Discworld, himself part of the Death of Universes, Azrael, a reference to the Islamic Angel of Death. He too has an independent part of him in the Death of Rats, the Grim Squeaker, whom he kept as companion after a period of death on the Discworld being taken care of by many sub-Deaths. Death can proceed through anything that is not endless like he is, as anything with an end is less real than him. Only a select few creatures, such as cats in general, which he dotes on, can see him, unless he pushes himself into their perception. He is part of the Four (sometimes five) Horsemen of the Apocalypse, but like him, they find mortals fun and don't care much to cause misery. All four like a good game of cards or similar activity and Death allows his clients a chance to prolong their lives by winning against him. Over time, Death has gathered a handful of mortal beings as family and live-in servants, who don't age as long as they are near him or his home.

Monster High

The Monster High grim reapers are River Styxx, her father, Charon, D'eath, G. Reaper, and Grimmie Reaper. The first four are all related, and the relation with the fifth, as well as his very existence, is unclear. Charon is River's uncle and implied to specifically be her father's brother. D'eath is the cousin of River's father (and presumably therefore of Charon too). [Source] D'eath and G. Reaper may be the same person, but the fiction is not conclusive on this. Grimmie Reaper is a Monster High alumn. [Source] In addition to these six, River berates the Ghosts of Hauntings for "messing with another reaper's confetti canons", insinuating that at least one of them is a grim reaper. If so, the logical candidate would be Future, who also has the skill of future vision [Source] just like confirmed grim reapers. [Source] In Monster High, River Styxx's father is the Grim Reaper and she is the niece of Charon. Since River Styxx is also related to Mr. D'eath, this must be that D'eath is also a ghost as well as a skeleton of the grim reaper lining.

In Monster High, grim reapers are exclusively psychopomps and not executioners or even announcers, although they do have a scythe and the gift of foresight. They are the only creatures able to travel between the Ghost World and Monster World by default and this means that nearly the entire species has the same occupation. For the most part, as beings who live in the Ghost World, their interactions are limited to ghosts, but they are able and expected to deal with solids too if the situation calls for it. As per Haunted and River's Haunted - Student Spirits diary, there's a reaper convention held in Las Plague-as, which given the seeming familiarity of the Monster High students might be located in the Monster World. The location's name is a portmanteau of Las Vegas and the Plague, which devastation brought in the 14th century is at the source of the creation of the Grim Reaper imagery.

D'eath is one of the original six Monster High employees Mattel introduced in 2010, though he belongs to the 2/3th to barely receive fictional presence. His 2010 appearances are limited to his inclusion in the Fearbook. The only information provided at this time was that he's the school counselor and attended North Styx State and Tombstone Tech to get the required degrees. In 2011, D'eath was not included in any fiction, but the sole appearance of G. Reaper occurred in "Back-to-Ghoul". He, too, is Monster High's school counselor. At this time, the characters could easily be the same person, but this started changing in 2012 when D'eath had a short spike in fictional presence due to inclusion in the Between Classes booklets and Ghoulfriends Forever and received characterization. D'eath is highly incompetent at his job, perpetually morose, enchanted by Scaris but psychologically unable to arrange to travel to there, and Rochelle hypothesizes he owns a cat. For as short as Reaper appeared in "Back-to-Ghoul", this does not match with his depiction, give or take owning a cat. In issue #10 of the UK magazine, released in January of 2013, a few pages were dedicated to the staff of Monster High, focussing on four of the original six. In case of D'eath, this included his credentials and art — published fully for the first time — but the name used was Reaper. This would imply again that the two are the same person, though D'eath's "attributes" as per the art are a newspaper and a cup of coffee, while as per "Back-to-Ghoul" Reaper carries around a scythe. Lastly, in Late 2014 River's Haunted diary complicated the situation again. According to it, reapers are bound by Oath of Neutrality, "By my scythe I do solemnly swear to use neither word nor deed to affect an outcome as yet undecided." River elaborates that any reaper who breaks this oath must give up their scythe and spend the next thousand years as a solid overthinking their deeds. This happened to her father's cousin, who's only identified as "a high school guidance counselor" nowadays. The full description matches D'eath perfectly, but it makes Reaper peculiar because he still has his scythe. It is possible that G. Reaper must be considered retconned as a fluke manifestation of D'eath, but equally if D'eath and Reaper have a dual identity going on like Jekyll and Hyde have, that would match all of the fiction regarding them so far. As aforementioned, the fiction is not conclusive on this.

D'eath's role a student counselor plays on the role of the Grim Reaper as psychopomp, as instead of helping the deceased through dying, D'eath helps students through high school. His once-enrollment at North Styx State is a reference to the river Styx, which in certain Roman adaptions of Greek mythology was the body that separated the realm of the living from the realm of the dead. River's last name, Styxx, also is a reference to the river. The ferryman who helped the deceased across the river for a fee, traditionally one coin, was Charon, whose tendency to leave coins everywhere bother's River's father. [Source] Rochelle's hunch that D'eath owns a cat is a shout-out to the Death of the Discworld novels. Though probably unintentional, both D'eath's friendship with Rochelle and false date with Sylphia Flapper in the Ghoulfriends Forever evoke the Death and the Maiden motif.

River Styxx was added to the franchise in the second half of 2014 and, as a full character, most on grim reapers in Monster High is established in material revolving around her, such as that grim reapers are classified as ghosts and why D'eath nonetheless lives in the world of the solids. River is a R.I.P., a Reaper In Preparation as pun on the phrase Rest In Peace, meaning that while she gets to carry around a stick, no blade is attached to it yet. She also is not able yet to see the future. Her father owns a ferry service in the Ghost World and he lets River help out in various ways so she can work to becoming a full reaper. River owns a pet raven, Cawtion, a creature commonly associated with death and dying. [Source]

Future is based on the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come from the novel A Christmas Carol. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is not necessarily Death, but likely inspired by the entity and rarely not interpreted as the same being. Future is in a similar situation, being dressed not unlike a funeral director and sharing the power of foresight with the confirmed reapers of Monster High, but he's also different in several ways. He does not have a skeletal appearance or a scythe or alternative tool like the confirmed ones. He also belongs to a group, of which the other two members have little going for a reaper identification, although this is the same as with Yet to Come among the Ghosts of Christmas. Coupled with the fact that ghosts are not well-defined in Haunted and that Future as an ally of Revenant is already operating outside of the rules of the Ghost World, it is not possible to say for certain whether he is a grim reaper or not.

Notes

- Like the Moirai, the Gorgons have also undergone triplication, with Medusa being the original.

- The poem of Lenore has been of high influence on the development of the vampire genre.

- Though created for different purposes independent of Doña Sebastiana, La Calavera Catrina also is a fusion of Native American customs and European ones.

- In the 1909/1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera, the titular phantom attends a ball dressed as the Red Death. The Phantom of the Opera also is an adaption of the Death and the Maiden motif.

External links

- La Mort dans l'Art

- The Death Card

- Psychopomps: Making a Road for the Spirit to Cross over

- The Gender of Death: A Cultural History in Art and Literature

- Death-defining personifications: the relatively stable representation of the Grim Reaper vs. the diachronic and synchronic variations in the representation of the Grande Faucheuse

- Godfather Death: Death in Fairy Tales by Terri Windling